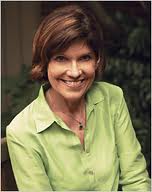

Lynne Olson, author of “Those Angry Days,” stopped by somuchsomanysofew to discuss her book and its exploration of the extreme polarization in the United States over the very idea of entering the war, an aspect forgotten by many people today.

Four of the books you’ve co-written or written focus on this specific period in World War II, when England was fighting alone. You’ve explored it from the point of view of the American journalists stationed in London, the Polish fighter pilots who joined the RAF, the men who brought Churchill to power, and with Those Angry Days you’ve come stateside to explain what was going on in the U.S. that was keeping us out of the fight. What is it about this particular aspect of the war that you find so compelling?I’ve been fascinated with both the place (Britain) and the period (the early days of World War II) ever since my husband, Stan Cloud, and I wrote our first book, The Murrow Boys, about Edward R. Murrow and the correspondents he hired to create CBS News before and during the war. Several scenes in the book take place in London during the Battle of Britain and the 1940-41 Blitz. In doing research for that book, I got caught up in the story of Britain’s struggle for survival in the early years of the war – and the extraordinary leadership of Winston Churchill and courage of ordinary Britons in waging that fight. I discovered that there were still a number of stories about the period that remained largely unknown and untold, so I decided to tell them myself.

Having focused so much on Britain in my previous books, I decided it was time, in my latest one, to take a look at the very bitter debate going on in the United States during 1939-1941 about what its role should be in World War II. It turned out to be an extraordinary story — one that I realized I didn’t know very much about and one that I don’t think most Americans do. That debate, as it turned out, was crucial in deciding the future of the United States, especially the role it would play in the world from then on.

As you’ve been touring with this book, have you faced a lot of surprise from readers? Specifically, that FDR was so reliant on polls, that Lindbergh held so many views which would make him wildly unpopular today?

I think what’s been most surprising to readers is the extreme polarization in this country over the very idea of entering the war. Today, we think of World War II as the “good war” — a necessary conflict to save Western civilization from the evil of Nazi Germany. And that’s all true. But in the years leading up to Pearl Harbor, the extent of that evil was not as obvious as it is now. The passions on both sides were really at a fever pitch.

As you indicate, there’s also considerable surprise about FDR’s caution and procrastination in taking bold, decisive steps that would move the country closer toward intervention. When most Americans think of FDR now, we think of his bold leadership, which he certainly did show in the first years of his presidency and then again after the United States got into the war. But during those critical years — 1939 to 1941 — while he was very forceful in his calls for action to help Britain and end German aggression, he sometimes dilly-dallied in making such action a reality. He tended to exaggerate the power of congressional isolationists and was quite reluctant to challenge them.

As for Charles Lindbergh, there’s no question that many of his views — on the role of Jews in our society, on race, on the importance of America remaining an isolationist country — would be anathema to a large proportion of Americans today. But what surprised me is how much those views reflected the mood of a significant segment of the population back then, a much greater percentage of the country than would be true now.

You see that scene in movies and tv shows of a sleepy America strolling home from church, or cheering at the Army-Navy game, suddenly stunned in to war. But in fact it had been a topic of ferocious debate for almost two years by then.

By December 1941, most Americans, I think, believed that the country was going to have to enter the war at some point. The big questions were: when and under what circumstances. I don’t think the majority of people in this country would have been surprised if our entry into the war had been triggered by a major incident involving Nazi Germany. After all, Hitler and the Nazis were regarded then as the biggest, most immediate threat to the United States and the world. Almost no one in the U.S. expected an attack on American soil by the Japanese. Getting into the war itself wasn’t unexpected; what shocked Americans were the stunning events that finally catapulted us into it.